Self-learning Of Historical Transverse Flutes

- Stefano Sabene

- Feb 14, 2025

- 4 min read

I am sometimes asked by flutists of all ages and skill levels whether it is possible to learn to play the Baroque 'traversiere' or the Renaissance and medieval transverse flutes on their own.

I try to provide an answer that is necessarily brief, but I hope it will be useful.

The simplest path for a trained flutist is to attend a specialized course, such as those now common in many early music departments at conservatories and music academies. However, the answer to the initial question is certainly and confidently yes! It is possible to learn to play historical instruments through self-study, but under certain conditions.

The first condition is to have a strong motivation. The second is to feel an irresistible attraction to these instruments and to early music. The third is to possess an insatiable musical curiosity.

Of course, I do not intend to go into detail here, as that would require much more space than a blog article can provide. What I will attempt is to outline, from a bird's eye view, a possible pathway to approach historical transverse flutes, encouraging the self-taught musician to interpret it in the most original and personal way possible.

The proof that such a journey is possible can be found in the pioneers of the rediscovery of ancient music. They had only copies of more or less reliable instruments at their disposal, while sources such as treatises and manuscripts were not always easily accessible in a time when musicological research was quite scarce and the internet did not yet exist.

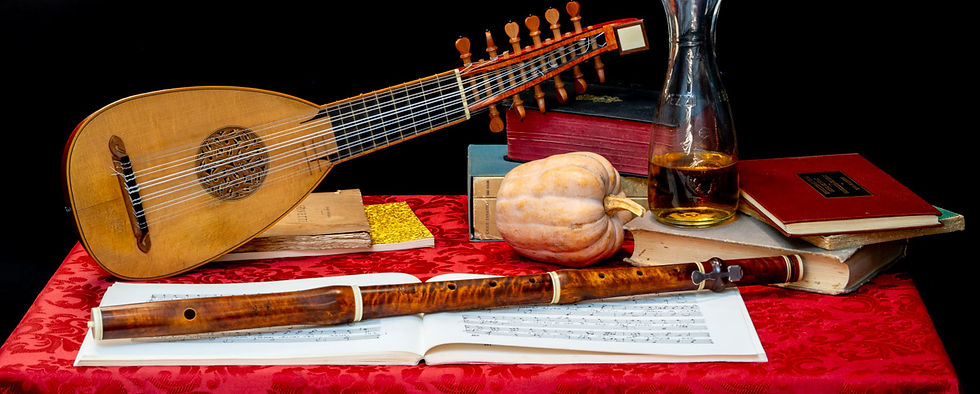

The Baroque 'Traversiere'

In my opinion, the most natural way for flutists transitioning from the modern instrument to approach historical instruments is to take a backward journey. At least, this has been my experience as a self-taught musician.

The Baroque traverso was an excellent starting point for me. Even a student model made of plastic, which is very affordable, will work just fine. Once the decision is made to fully commit to this path, one can then acquire a professional instrument.

The most evident difference, compared to the modern flute, aside from the completely different construction material, lies in the embouchure, which features a much smaller hole that is predominantly round in shape and lacks the comfortable support of a lip plate. Musicians will need to come to terms with this embouchure right away, but after the initial encounter— which may be challenging— a satisfactory sound production will soon follow.

Another tactile difference is the absence of keys, except for the right-hand pinky key, along with the disconcerting lack of holes for the left thumb, which, along with the pinky, will remain inactive. The holes will be covered directly by the fingertips of the remaining fingers. This sensation can be quite pleasant once the finger positioning over the distances of the holes is established.

With the traverso, one will also become aware of the necessity to adjust the intonation of certain notes, in a context that is no longer equal temperament. However, the truncated conical section of the instrument, along with the presence of the key, will make intonation easier compared to the Renaissance and medieval traversos, which are cylindrical and lack keys.

The initial approach can begin with the production of long notes (sustained sounds, "messa di voce"), and the practice of scales and arpeggios, experimenting with various types of tonguing techniques. This will lead to increasing familiarity with fingering and sound production across different registers, aiming for timbral uniformity. Gradually progressing in terms of alterations and technical complexity, one can relatively quickly gain a certain mastery of the instrument, allowing for the exploration of initial pieces of music, starting with the abundant repertoire dedicated to amateur musicians of the time, before moving on to the works of major composers (Bach, Handel, etc.).

Reading directly from ancient prints will help to immerse oneself in the spirit of the period, as will an in-depth engagement with treatises, beginning with the relatively simple essay by Lorenzoni, which includes fingering charts, and then progressing to more substantial works, such as the fundamental and monumental treatise by Johann Joachim Quantz, a valuable source of information not only on flute performance but also on the theory and practices of the time. A considerable quantity of sources, including facsimiles, can be found online.

Of course, listening to the best interpreters, whether through recordings or various online formats, will only enhance the level of performance and the assimilation of Baroque musical aesthetics, which is tied to the theory of "affections."

Consistent and in-depth work, which does not have a definitive endpoint but continues in a pursuit of knowledge, will eventually lead to the development of a personal style.

The Renaissance Transverse Flute

In introducing the Renaissance flute into instrumental practice, the experience gained with the Baroque traverso will allow for relatively quick and appreciable results. The sound production is quite similar, while the fingering differs significantly due to the absence of keys. However, the musical aesthetics of the Renaissance is entirely different, presenting a contrapuntal complexity that contrasts with the melodic and soloistic interest typical of Baroque music.

Once comfortable with the fingering, musicians will soon be able to tackle relatively simple pieces, such as dance music, while simultaneously studying treatises that introduce essential topics like modal harmony, mensural notation, and the practice of diminutions.

Alongside the skills developed with the traverso, additional concepts and techniques will need to be learned, as they are fundamentally and executively distinct. This includes practices such as diminutions, ornamentation, temperaments, along with a multitude of aspects related to Renaissance musical forms.

The Medieval Transverse Flute

Finally, one will turn to the medieval transverse flute, which is organologically quite similar to the Renaissance traverso.

This instrument will present flutists with the need for new knowledge, less pressing on the technical and performance aspects, but very challenging in terms of theory, aesthetics, and cultural understanding.

Conclusions

As mentioned, this brief article does not aspire to outline an exhaustive pathway that is valid for every flutist, but rather serves as one approach—hopeful of being somewhat useful—to present the self-taught musician with the issues they will face.

However, I can assure you that the rewards of self-learning are immense, and as is often the case, the most gratifying aspect is not the accomplishment of the goal, but the journey taken to achieve it.

Un percorso d'apprendimento davvero stimolante. La dedizione necessaria per lo studio dei flauti storici e la consultazione dei trattati antichi citati nell'articolo richiedono una grande capacità di analisi testuale. Per facilitare lo studio di questi documenti tecnici, analisi logica rappresenta uno strumento professionale per studiare e comprendere la struttura delle frasi in modo rapido ed efficace. Questa soluzione digitale offre un supporto affidabile a studenti e docenti che desiderano approfondire la grammatica e la sintassi con praticità, rendendo l'interpretazione dei testi complessi molto più accurata.

analisi logica online è uno strumento professionale progettato per studiare e comprendere rapidamente la struttura delle frasi italiane. Grazie a piattaforme digitali avanzate, permette di identificare con precisione soggetto, predicato, complementi ed altre funzioni sintattiche, rendendo l’apprendimento della grammatica più chiaro e immediato. Questa soluzione digitale rappresenta un supporto affidabile per studenti, docenti e professionisti che vogliono approfondire le proprie competenze linguistiche con praticità e accuratezza. Con analisi logica online, ogni frase viene analizzata in pochi secondi, offrendo spiegazioni dettagliate e leggibili, trasformando lo studio della grammatica italiana in un’esperienza semplice ed efficace.

analisi logica online rappresenta uno strumento professionale per studiare e comprendere la struttura delle frasi in modo rapido ed efficace. Attraverso piattaforme dedicate, è possibile identificare con precisione soggetto, predicato, complementi e altre funzioni sintattiche. Questa soluzione digitale offre un supporto affidabile a studenti, docenti e professionisti che desiderano approfondire la grammatica italiana con praticità e accuratezza.